What Are Accounting Adjustments?

Many or all of the products featured here are from our partners who compensate us. This influences which products we write about and where and how the product appears on a page. However, this does not influence our evaluations. Our opinions are our own. Here is a list of our partners and here's how we make money.

Adjusting entries are made at the end of the accounting period to make your financial statements more accurately reflect your income and expenses, usually — but not always — on an accrual basis. This can be at the end of the month or the end of the year.

If you have adjusting entries that need to be made to your financial statements before closing your books for the year, does that mean your books aren't as accurate as you thought? This article will take a close look at adjusting entries for accounting purposes, how they are made, what they affect and how to minimize their impact on your financial statements.

FEATURED

Adjusting entries defined

In order to maintain accurate business financials, you or your bookkeeper will enter income and expenses as they are recognized in your business. This can be done on either a cash basis or an accrual basis.

Regardless of how meticulous your bookkeeping is, though, you or your accountant will have to make adjusting entries from time to time. An adjusting entry is simply an adjustment to your books to better align your financial statements with your income and expenses.

Adjusting entries are made at the end of the accounting period. This can be at the end of the month or the end of the year. Your accountant will likely give you adjusting entries to be made on an annual basis, but your bookkeeper might make adjustments monthly.

How adjusting entries are made

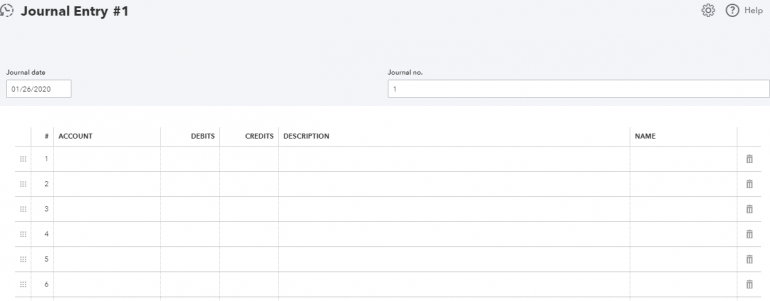

Adjusting entries are typically made using a journal entry. If you use small-business accounting software — like QuickBooks, Xero or FreshBooks — you might not be familiar with journal entries. That’s because most accounting software posts the journal entries for you based on the transactions entered.

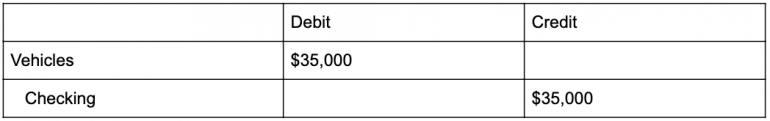

Double-entry accounting stipulates that every transaction in your bookkeeping consists of a debit and a credit, which must be kept in balance for your books to be accurate. Your accounting software takes care of this for you. For example, when you enter a check in your accounting software, you likely complete a form on your computer screen that looks similar to a check. Behind the scenes, though, your software is debiting the expense account (or category) you use on the check and crediting your checking account.

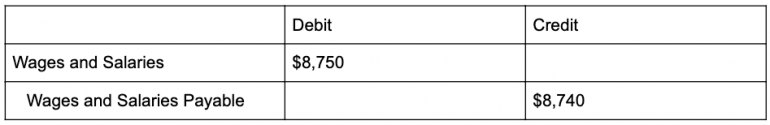

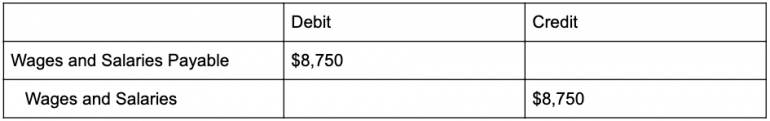

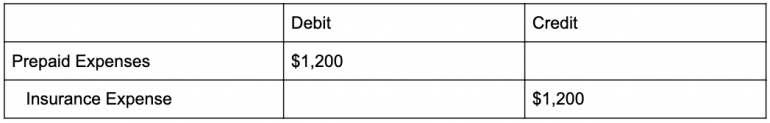

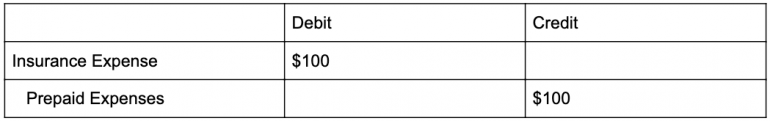

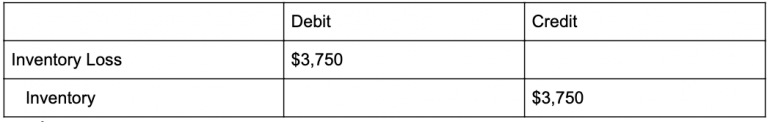

When you make a journal entry, the automated component is stripped away, and you are left with something that looks like this:

Types of accounting adjustments

Adjusting entries usually involve one or more balance sheet accounts and one or more accounts from your profit and loss statement. In other words, when you make an adjusting entry to your books, you are adjusting your income or expenses and either what your company owns (assets) or what it owes (liabilities).

Adjusting entries usually fall into one of four categories:

Accruals

Most accruals will be posted automatically in the course of your accrual basis accounting. However, there are times — like when you have made a sale but haven’t billed for it yet at the end of the accounting period — when you would need to make an accrual entry.

Another common accrual happens at year-end. Let’s say you pay your employees on the 1st and 15th of each month. At year-end, half of December’s wages have not yet been paid; they will be paid on the 1st of January. If you keep your books on a true accrual basis, you would need to make an adjusting entry for these wages dated Dec. 31 and then reverse it on Jan. 1.

Deferrals

In practice, you are more likely to encounter deferrals than accruals in your small business. The most common deferrals are prepaid expenses and unearned revenues.

Let’s say you pay your business insurance for the next 12 months in December of each year. You have paid for this service, but you haven’t used the coverage yet. This would be recorded as a prepaid expense in your books.

Or perhaps a customer has made a deposit for services you have not yet rendered. You are holding their money, but you haven’t earned it yet. This would be posted as unearned revenue in your books.

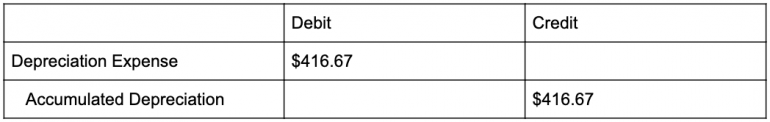

Depreciation and amortization

For tax purposes, your tax preparer might fully expense the purchase of a fixed asset when you purchase it. However, for management purposes, you don’t fully use the asset at the time of purchase. Instead, it is used up over time, and this use is recorded as a depreciation expense. Whereas you’d record a depreciation entry for a tangible asset, amortization is used to stretch the expense of intangible assets over a period of time.

Depreciation and amortization are common accounting adjustments for small businesses.

Estimates

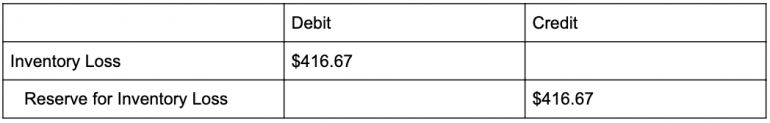

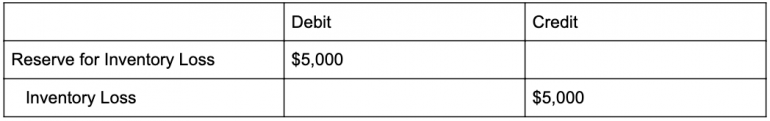

Some businesses set up reserve accounts for expenses they think their company might incur, but they don’t have an actual amount yet. Two common estimate entries are for bad debt allowance: the portion of accounts receivable that the business estimates might be uncollectible based on its A/R collection history; and inventory spoilage/loss, or the amount of inventory the business estimates it will lose due to spoilage, obsolescence, theft or some other non-revenue activity.

When to make adjustments in accounting

Adjusting entries are typically made after the trial balance has been prepared and reviewed by your accountant or bookkeeper. Sometimes, your bookkeeper can enter a recurring transaction, and these entries will be posted automatically each month before the close of the period.

Other times, the adjustments might have to be calculated for each period, and then your accountant will give you adjusting entries to make after the end of the accounting period. Either way, make sure you understand the purpose of the entry.

Having adjusting entries doesn’t necessarily mean there is something wrong with your bookkeeping practices. If you are concerned something might be amiss, speak with your accountant; they will be able to tell you if something needs to be changed in your bookkeeping processes to reduce the need for adjusting entries.

Bookkeeping and accounting software | |

|---|---|

QuickBooks Online $30 per month and up. Read Review. | |

FreshBooks Accounting $17 per month and up. Read Review. | |

Xero $13 per month and up. | |

Zoho Books $0 per month and up. | |

Sage 50 Accounting $48.17 per month (when paid annually) and up. | |

Wave Financial Free (add-ons available). | |

A version of this article was first published on Fundera, a subsidiary of NerdWallet.

| Product | Starting at | Promotion | Learn more |

|---|---|---|---|

QuickBooks Online NerdWallet Rating Learn more on QuickBooks' website | $30/month Additional pricing tiers (per month): $60, $90, $200. | 50% off for first three months or free 30-day trial. | Learn more on QuickBooks' website |

Xero NerdWallet Rating Learn more on Xero's website | $15/month Additional pricing tiers (per month): $42, $78. | 30-day free trial or monthly discount (terms vary). | Learn more on Xero's website |

Zoho Books NerdWallet Rating Learn more on Zoho Books' website | $0 Additional pricing tiers (per month): $20, $50, $70, $150, $275. | 14-day free trial of the Premium plan. | Learn more on Zoho Books' website |

FreshBooks NerdWallet Rating Learn more on FreshBooks' website | $19/month Additional pricing tiers (per month): $33, $60, custom. | 30-day free trial or monthly discount (terms vary). | Learn more on FreshBooks' website |